Abstract

We create a fly simulation in which flies must navigate a simple maze to find food. Evolved flies saturate this benchmark (reach 100%) - but only after we culled long inference times. We include steps for reproducibility, so that our paper is easily replicated.

Keywords

AI, inference, evolution, crossover, backpropagation, transformer

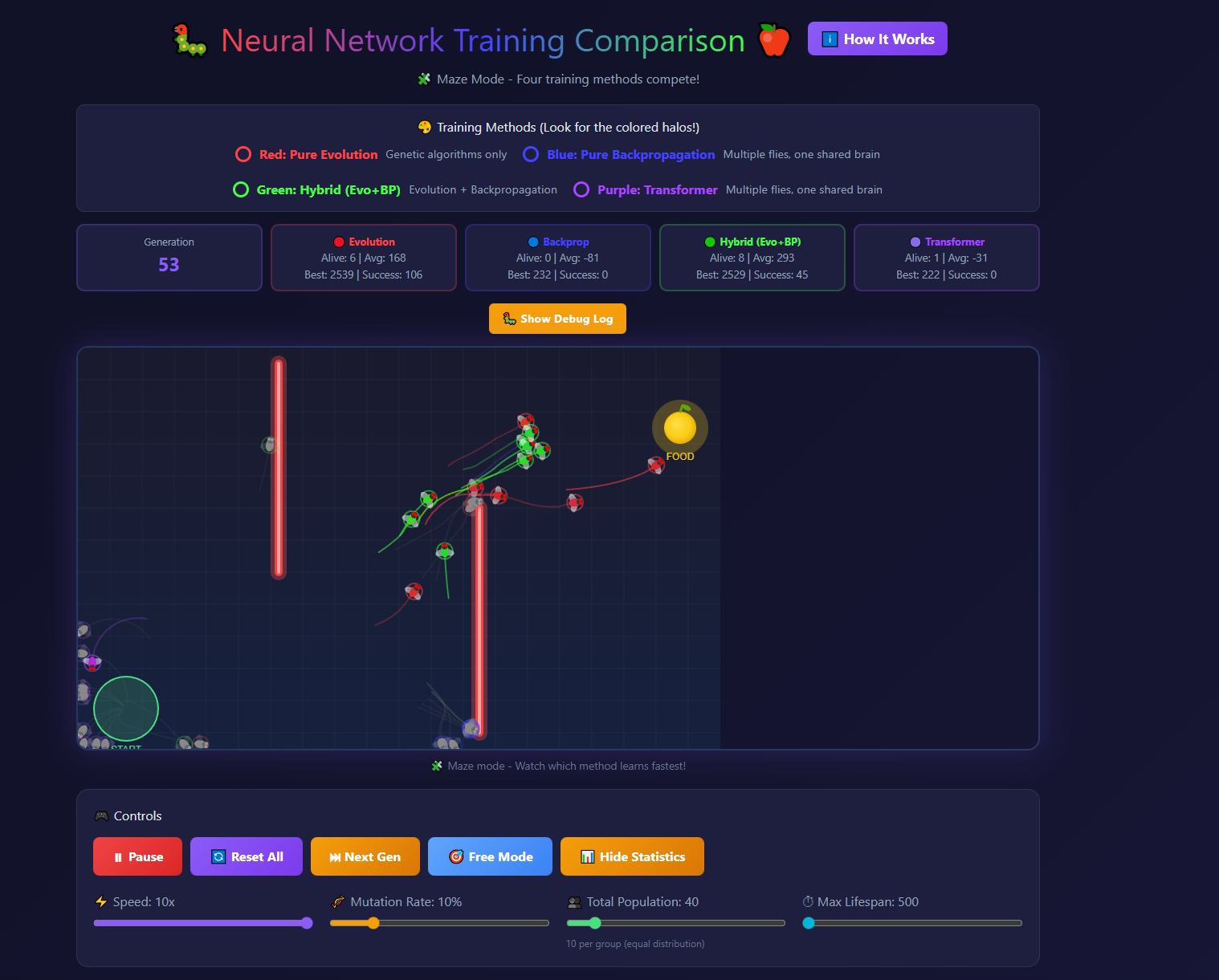

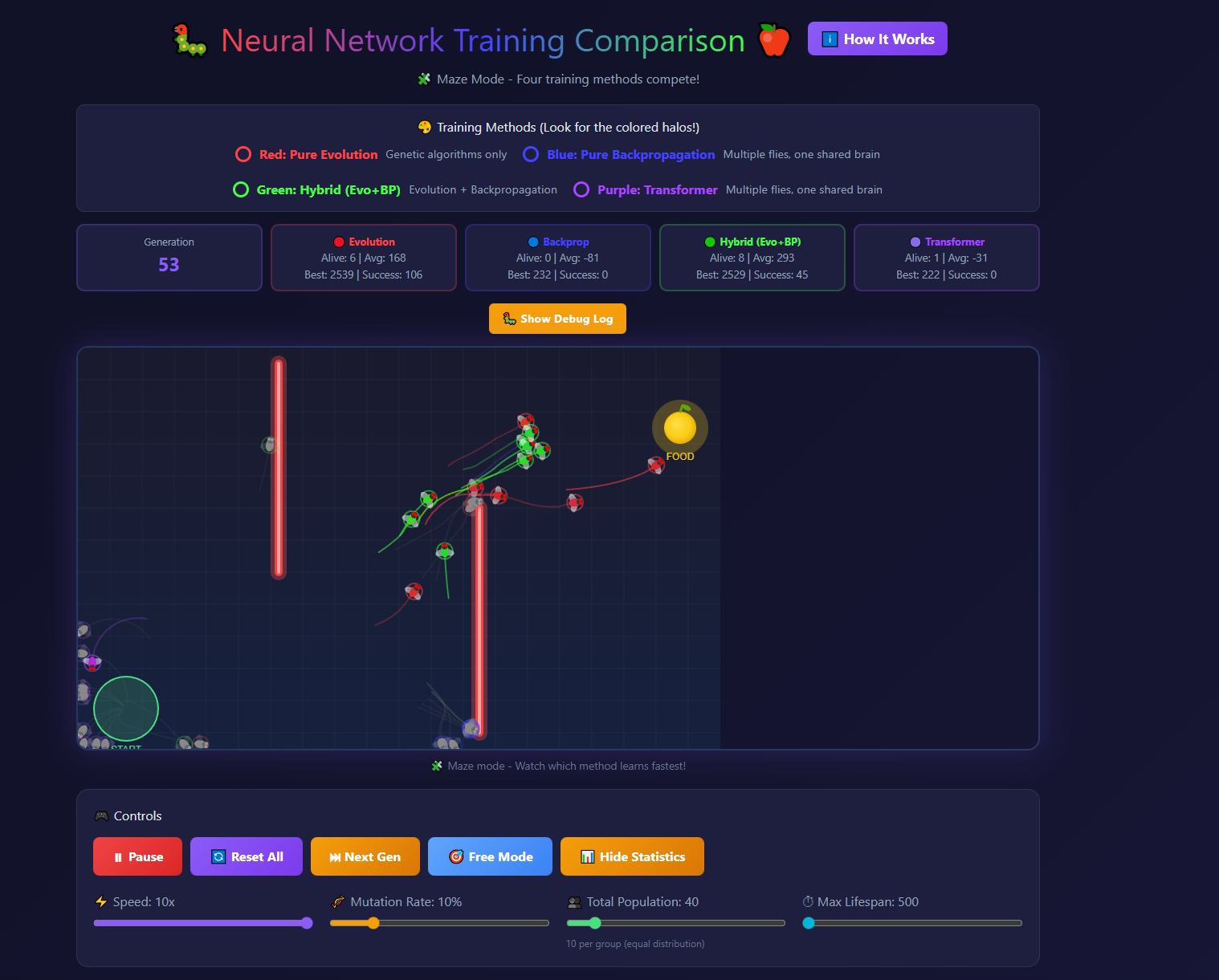

Figure 1: the simulated environment

1. Introduction

We create an interesting game to evolve fruitfly brains. The complete game/simulation is available here. (click "Maze Mode" for the obstacle course, and click "Show Statistics" to show statistics. You can adjust hyperparameters. Don't miss pausing it and clicking one of the flies, to show an amazing brain visualization of all its parameters - not included here to avoid spoilers.)

We shared it once during development, and it received 14 upvotes on Hacker News. We wanted to see flies evolve to reach food through obstacles, so subsequent to the release of that version, we simplified the maze to be a simpler obstacle course.

2. Methodology

After creating the game, we tried various hyperparameter settings. We noticed that near the end of each generation, some flies were headed directly for the food and would have reached it if not culled. Therefore we increased the lifespan. In our view at the time, it was more important to optimize for course completion than speed, and this would allow more of the population to reach food. To our great frustration, after maximizing the lifespan hyperparameter to 5,000, learning stopped at the point that only 50% of the flies were able to reach the food. We wanted to know: why weren't our flies learning? Observing the playing field, we noticed that flies were all engaging in unproductive spinning behavior, spinning around quickly, as shown in this figure:

Figure 2: flies spinning unproductively.

We wondered what would happen if we reduced the lifespan somewhat, so we did so within the same experiment. Almost immediately, the flies' fitness improved.

Figure 3: paradoxically, flies' fitness improved with a shorter lifespan (yellow lines mark where we decreased lifespan)

Next we decided to limit the flies' lifespan dramatically, to just short enough to complete the course. Amazingly, this resulted in a far higher percentage of flies reaching the food, and the flies were no longer engaging in unproductive spinning behavior. To us, this is an almost paradoxical result, since there was nothing stopping flies from flying straight to the food even with the long lifespan. What happened in fact is that only after reducing the lifespan were flies able to reach the food.

3. Results

With the lifespan minimized to just long enough to complete the obstacle course, fitter flies evolved almost immediately, and in some generations were able to saturate the benchmark, achieving 100% survival rate.

4. Reproducibility

We encourage others to reproduce our results: open the linked simulation, and try evolving flies, giving them a long lifespan, 5,000 steps. Once you see that the survival rate is capped at a low percentage, such as 50%, you can notice that all the flies have evolved maladaptive spinning behavior. The flies spin around, and don't make it to the food. Then, you can reduce the lifespan and can notice that much more fit flies evolve. By reducing the lifespan aggressively to just long enough to complete the course, you will see that the flies engage in highly adaptive behavior, and may be able to briefly saturate the benchmark (achieving 100%).

5. Discussion

Achieving 100% survival rate by aggressively culling flies by shortening their life span is a paradoxical result. How can more flies survive if we're culling them before they've reached the goal, even if they would have reached it eventually? This paradoxical result could explain why humans don't live for 500 years, but are naturally culled around 100 by several mechanisms. As ChatGPT put it:

Replicative senescence via telomere attrition enforced by tumor suppression.

In practice:

- Most somatic cells lack telomerase. the enzyme in a eukaryote that repairs the telomeres of the chromosomes so that they do not become progressively shorter during successive rounds of chromosome replication.

- Telomeres shorten with division.

- Critically short telomeres trigger p53-mediated senescence or apoptosis.

- This progressively disables tissue regeneration across organs.

- Telomerase repression + aggressive cancer surveillance makes the failure systemic and irreversible.

It's not a timer, but it functions like one: a hard architectural limit that guarantees organismal breakdown after sufficient time, chosen because relaxing it explodes cancer risk earlier.

6. Efficiency advantage

After publication of this result, this comment points out the computational advantage. A lifetime of 5,000 steps takes up to 5x longer to run than lifetimes of 1,000, and therefore the latter is up to 5x more efficient, which is a great advantage in case of a fixed set of computational resources. So, not only do you get fitter flies, but it takes only a fraction of the time.

7. Limitations

This is one result in a simulated environment. It is possible that the result does not generalize.

8. Conclusion

In the simulated obstacle course, long lifespan became a population-level liability, resulting in all the flies spinning unproductively, with only half of them ever making it to food. Culling them with a hard limit of how long the obstacle course should take resulted in objectively and subjectively fitter flies that complete the obstacle course with ease, at times saturating this benchmark. The key lesson is: when using evolutionary algorithms to train neural nets via evolutionary crossover, don't give them more time than the course should take, or they will develop unproductive behaviors. Whether it's playing a game or doing some other task, given too long to do it, maladaptive behaviors arise. Instead, give brains in each generation just enough time to complete the course.

9. Future Work

The present implementation is dominated by a simple crossover architecture, a simple backprop architecture, and a hybrid of both approaches. It would be interesting to add a full transformer architecture with many layers - the transformer flies currently have only a single hidden layer for performance reasons.

Appendix

Full system overview

A full system overview is included in the application. Press "How It Works" to see it.